Election 2022: Climate and energy

Policy performance and promises1

Peter Christoff2

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and a range of other scientific assessments clearly state that the window of opportunity is almost closed if we are to stop global warming rising to catastrophic levels. Yet this election seems – at least for the major parties – to be less about climate change than any other in the past 15 years.

Climate is no longer the focus of brutal political contest – as in 2010, 2013 and 2016 – when governments were partly elected and leaders deposed over the issue. This time there is no push by Labor to establish an emissions trading scheme, no Greens cavalcade into Queensland’s coal-mining hinterland, and no prevarication by the major parties over the Adani mine and coal and gas exports. The contest in 2022 is mainly over other issues – leadership integrity, economic management and the cost of living, and now regional security.

In this election, we can expect the ‘climate vote’ to be driven by several factors. They include:

- personal experience of disaster and recovery

- Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s leadership on the issue

- the government’s performance in reducing emissions, power prices and energy security

- competing parties’ and independents’ credibility and policy promises on climate action.

This briefing paper looks at each of these factors, predominantly reviewing major emissions mitigation actions, policies and promises. It shows clear differences between the contending parties and independents.

The Morrison government’s policies and promises fall far short of what is required for Australia to contribute equitably to the effort of keeping global warming below 1.5° Celsius. Their 2030 emissions target remains by far the weakest among all major developed countries.

The Australian Greens’ and climate independents’ emissions targets are significantly stronger than those of Labor, and all are stronger than the Coalition’s. The Greens and Labor’s renewable energy and electric vehicle policies are also, overall, far more ambitious than the Coalition’s.

The climate vote

Climate change determines how an increasing proportion of Australians vote – around 13 per cent in 2019.3 Several polls4 suggest climate remains a defining issue for voters this time around. If they’re right, the Coalition – with its bare majority – is in trouble. Of course, it’s not the overall swing that counts, but what happens in a handful of marginal seats.

Of the 25 or so electorates likely to determine the next result, seven were hard hit by the Black Summer fires and the 2022 floods. Five are marginal ALP seats – Dobell, Eden-Monaro, Macquarie and Gilmore in NSW, and Lilley in Queensland. If climate impact has an influence on voting, it will help secure Labor incumbents in these marginal seats, some of which the Coalition is hoping to tip. The other two – Page in NSW and Gippsland in Victoria – are safe Nationals seats.

There are also several inner urban seats where Independents campaigning on climate policy and backed by the Climate 200 movement may cause losses for the Liberal Party. These include Goldstein in Victoria where Zoe Daniel is challenging incumbent Tim Wilson (margin of 7.8 per cent); and in NSW, Wentworth with Allegra Spender versus incumbent Dave Sharma (1.4 per cent) and North Sydney with Kylea Tink against incumbent Trent Zimmerman (9.3 per cent).5 Less likely but possible is Kooyong, where Monique Ryan is standing against Treasurer Josh Frydenberg (5.7 per cent). If these seats respond to climate issues, the Coalition is in trouble. (Meanwhile Zali Steggall, the incumbent climate independent in Warringah, increasingly looks secure.)

Climate anxiety, experience and emergencies

Public anxiety over future climate impacts is growing. The Lowy Institute reports that 60 per cent of Australians now say global warming is a significant and pressing problem.6 This figure is comparable to when the Morrison government was elected (61 per cent in 2019).

Although overshadowed by the COVID-19 pandemic, the current Morrison government term has been framed by extreme events fuelled by global warming – first the Black Summer bushfires that began in 2019, and now the floods. The Black Summer fires were unprecedented in extent and intensity in Australia’s documented history.

The number of Australians directly affected by climate-enhanced extreme events during a single term of government is at an all-time high. More than 13 million people – over half of all Australians, including the inhabitants of every capital city and major settlement on Australia’s eastern coast – were affected by the smoke of the Black Summer fires, and the longer-term health impacts of that event are yet to fully emerge. The major floods of 2022 hit Brisbane and parts of Sydney, as well as numerous rural cities and towns, added to the trail of economic devastation caused by COVID-19.

The evidence for extreme weather affecting attitudes and voting intentions is mixed.7 A comparison study of 58 middle- to high-income countries over the period 2008–2017 found that the effect of major climate-related disaster events, only led to greater climate action in ‘highly functioning democracies’ and the political effects of extreme weather dissipated after a year.8

However, if economic considerations come to the fore and persist, it is likely that voter response in the hardest hit electorates will be focused on the material impacts of disaster response and associated agency performance.

Although disaster response involves both State and Commonwealth mechanisms and processes, the entrenched public view in affected electorates – and associated media narrative – is of late and weak activity by federal government agencies. This will weigh against the Coalition in marginal seats.

Climate leadership and credibility

Australian elections have become more presidential in style: leadership polls with increasing media focus on the party leader’s history, personality and, where relevant, personal performance.

With climate change, Scott Morrison has a credibility problem, having ‘defined’ himself while Treasurer by triumphantly brandishing a lump of coal in Parliament.9 As PM, he projects a lack of understanding about the need for emissions reduction and limited empathy and concern about global warming’s catastrophic impacts.

Questions about his understanding of the symbolic and practical roles of a political leader during crises arose specifically in relation to climate-fuelled extreme events. A YouGov online survey of 1033 people between 8 and 12 January 2020, commissioned by the Australia Institute, found that 82 per cent of those directly impacted by the fires, and 59 per cent of those not directly impacted, agreed that ‘Leadership on the bushfire response requires the Prime Minister to lead on climate action’.10

Prime Minister Morrison’s initial absence on a holiday trip to Hawaii during the Black Summer fires continues to haunt his reputation, particularly in fire-affected electorates, and his government’s responses to the recent floods were surprisingly sluggish given the Black Summer fires debacle.

The Prime Minister did not deny the science of climate change and conceded that the Black Summer fires were part of a broader pattern of more extreme weather attributed to climate change.11

Notably, the Morrison government’s political management of this issue – and Labor’s retreat from key policies, such as putting an explicit price on carbon and employing an emissions trading scheme to do so – has greatly reduced the levels and excesses of conflict over climate and energy issues that preceded its term of government. In addition, COVID-related regulatory restrictions on public gatherings and association through schools and workplaces greatly reduced the potential for collective mobilisation around this issue.

Together, these effects have effectively thrown a blanket over public concern about climate change and limited its expression to exchanges on social media. This reduction in the public profile of the issue may benefit the Coalition.

Climate and energy policy performance

Elections favour incumbents if their performance is good – which is why it is often said that governments lose elections rather than oppositions winning them. Here we examine key elements of the Morrison government’s domestic and international climate-related performance since it was elected in May 2019.

Emissions

The headline performance indicator for climate policy is the change in volume of national emissions. Australia’s domestic greenhouse emissions for the year to December 2019 were estimated to be 532.5 Mt CO₂-e.12 By September 2021 emissions were estimated to have fallen to 501.5 Mt CO₂-e .13 That is an overall decline of some 9.4 per cent during the term of the Morrison government.

National emissions in the year to September 2021 were therefore also 19.8 per cent below emissions in the year to June 2005, the baseline year for Australia’s 2030 target of -26–28 per cent under the Paris Agreement.

This decline cannot be attributed mostly to national policy. Rather, it strongly reflects the additional and unanticipated impacts of COVID-19 on social and economic activity, including on energy consumption and transport particularly in 2019–2020 and especially through major lockdowns in Victoria and NSW.14

The latest National Greenhouse Inventory report (September 2021) notes this decline includes:

- ongoing reductions in emissions from electricity (down 4.7 per cent from September 2020)

- lower fugitive emissions (down 5.1 per cent), resulting from declines in coal production

- increased transport emissions (up 1.4 per cent) reflecting a gradual recovery from the impacts of COVID restrictions on movement

- increased emissions from stationary energy excluding electricity (up 1.7 per cent), driven by an increase in fuel combustion in the manufacturing sector

- increased emissions from agriculture (up 3.8 per cent) due to the continuing recovery from recent drought.15

Prime Minister Morrison says we will meet and exceed Australia’s current 2030 target of 26–28 per cent below 2005 levels.16 However, the likelihood of meeting its target has been questioned in recent modelling, which looks beyond the annual emissions to the total quantum of emissions implied over the period from 2005 to 2030.17 This projected failure reflects the inadequacy of national (and subnational) policies and goals to even achieve the current modest mitigation goal.

Australia’s 2030 target is by far the weakest among major developed countries (Table 1).

Table 1: Developed countries’ 2030 emissions targets

Country | 2030 target |

Australia | -26–28% below 2005 level |

Canada | -40–45% below 2005 level |

EU | At least -55% below 1990 level |

France | -40% below 1990 level |

Germany | -65% below 1990 (ex LULUCF) |

Japan | -46% below 2013 level |

New Zealand | -50% below 2005 level |

Norway | At least -50% and towards -55% below 1990 level |

Russian Federation | -30% below 1990 level |

South Korea | -40% below 2018 level |

Sweden | -63% below 1990 level |

Switzerland | -30% below 1990 level |

United Kingdom | At least -68% below 1990 level |

United States | - 50–52% below 2005 level (including LULUCF) |

Target commitments under the Paris Agreement (at April 2022)

Renewables

A second major indicator of successful climate and energy policy is the shift to renewables and away from fossil fuels for electricity generation.

Australia’s Renewable Energy Target (RET) was a federal government policy intended to ensure 33,000 gigawatt hours of Australia’s electricity came from renewable sources by 2020. Australia met this target in September 2019, a year ahead of schedule.18 The target expired in 2020 and has not been extended.

Some 24 per cent of electricity came from renewables in 2020. This reflects an increase of 15 per cent in renewables’ contribution in 2019–2020 – involving a 42 per cent increase in solar generation and 15 per cent increase in wind generation, with solar and wind each contributing 8 per cent of total generation. Solar Photovoltaics (PV), especially large-scale solar PV, was the fastest growing generation type in both 2019–20 and the 2020 calendar year.19

The Morrison government has claimed responsibility for Australia’s emissions trajectory and this transition to renewables. However, it has been the states’ and territories’ tough targets and supportive policies, coupled with the dynamism and market competitiveness of renewable energy technologies, that have led to the decline of coal-fired power generation.20

States’ and territories’ regulatory measures and material assistance have encouraged a record shift by households and businesses to rooftop solar, and also substantial private-sector investment in large-scale renewables and batteries. The new economics of the power generation sector has ended new investment in coal- and gas-fired power, caused a major decline in maintenance expenditure, and accelerated the closure of existing coal-fired power stations.

The Morrison government’s attempts to reinforce energy security have been problematic, including by trying to force the owners of the Liddell power station to delay its proposed closure in 2022 (now 2023). In this context, its support for gas-fired ‘recovery’ – including replacement generation at Tallawarra and Kurri Kurri21 – makes little economic or ecological sense.

The government has provided initial funding for new technologies and fuels, particularly hydrogen. In adopting the National Hydrogen Strategy22, it has committed to developing ‘hydrogen hubs’ where hydrogen will be produced, or used or exported. The development of the hydrogen industry may take a decade or longer, with the period to 2025 being used for pilots, trials and basic infrastructural development, with the intention of scaling up activity after then. To do so, it has sought to enable the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) to fund hydrogen-from-gas and carbon capture and storage, which may prolong the use of gas.23

Promises made in 2019 to address grid reliability through the Underwriting New Generation Investments (UNGI) program24, supported by a promised legislated AU$1 billion Grid Reliability Fund, have not been kept.25

The Government's flagship multi-billion-dollar carbon credit scheme – the Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) – has been criticised as systematically flawed, with 70 to 80 per cent of the carbon credit units issued to these projects being devoid of integrity (ie they do not represent real and additional abatement).26

It is highly unlikely that the scheme has limited emissions to the extent claimed. Professor Andrew Macintosh, who chaired the Integrity Committee of the ERF, has called it ‘a fraud on the environment, a fraud on taxpayers, and a fraud on unwitting private buyers’.27 In any case, given the need to reduce carbon emissions absolutely the concept of carbon offsetting is deeply problematic.

Fossil fuel exports

Australia is the world’s largest exporter of metallurgical coal and natural gas, the second largest exporter of thermal coal (after Indonesia), and the third largest exporter of fossil fuels overall. Australia’s net fossil fuel exports (exports minus imports) were equal to 70 per cent of its production in 2019–20. Energy exports grew by 2 per cent in 2019–20. LNG exports grew by 6 per cent.28

It is often claimed that Australia’s contribution to climate change is trivial. Its coal and gas exports embody more than twice our domestic emissions. These exported emissions, when added to domestic emissions, make Australia the world’s sixth largest source of CO₂-e emissions.

Morrison government policies have encouraged the growth of Australia’s fossil fuel exports, including through the provision of tax breaks and subsidies.29

International profile and performance

Historically Australia has had a poor international reputation in the field of international climate negotiations, beginning with its intransigent behavior in securing an exceptionally weak target during the negotiation of the Kyoto Protocol in 1997.30

This reputation has been further entrenched during the period of the Morrison government. Only through exceptional domestic and international pressure did the Morrison government resile from using ‘surplus credits’ from its 2020 emissions target to further soften mitigation towards its 2030 target.31

Australia’s adoption of its Net Zero by 2050 target was painfully slow and grudging, with the Morrison government having to overcome strong resistance from its Coalition partner, the Nationals.

Under the Paris Agreement, Australia’s already comparatively weak 2030 emissions target of -26–28 per cent below 2005 levels – set by the Abbott government in 2015 – should have been toughened at the UN climate conference in Glasgow last year. PM Morrison’s refusal to do so meant Australia fell further behind other developed countries.

At Glasgow, Australia also refused to sign joint pledges to reduce methane emissions, to phase out coal power during the 2030s or as soon as possible, and to end overseas investment in coal, oil and gas.32

Australia’s performance had reputational costs and led it to be branded a laggard at the 2021 UN Climate Summit in Glasgow33 and labeled by the UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres a ‘holdout’ for its weak target.34

Policy promises

The policy promises each party and independent brings to this election should be considered in relation to the core challenge of dealing with global warming.

The IPCC’s latest reports and related scientific modeling indicate that to keep global warming to below 1.5° Celsius (global average increase), total emissions need to peak immediately, followed by a sharp decline in total emissions (by some -43% by 2030) reaching Net Zero by no later than 2050.35

Collectively, current commitments by parties to the Paris Agreement – if met – would still see warming increase by about 2° Celsius. Even then, this rate of emissions reduction leaves a significant (50 per cent) chance that warming will exceed not only 1.5° Celsius but also 2° Celsius.

Elections favour those with a strong narrative about the future and policy commitments to match. The road to elections is paved with broken old campaign promises and lit by bright new ones.

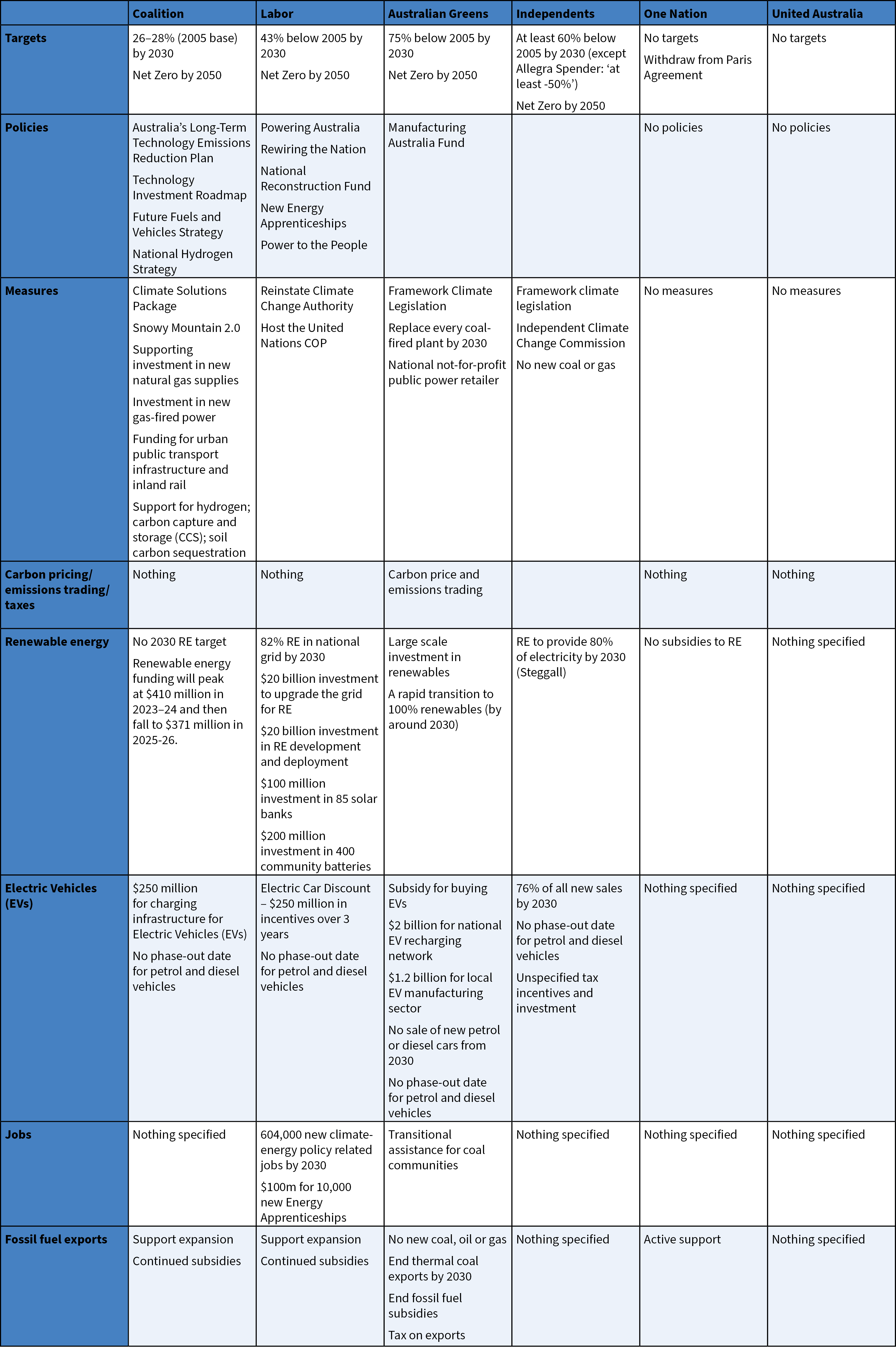

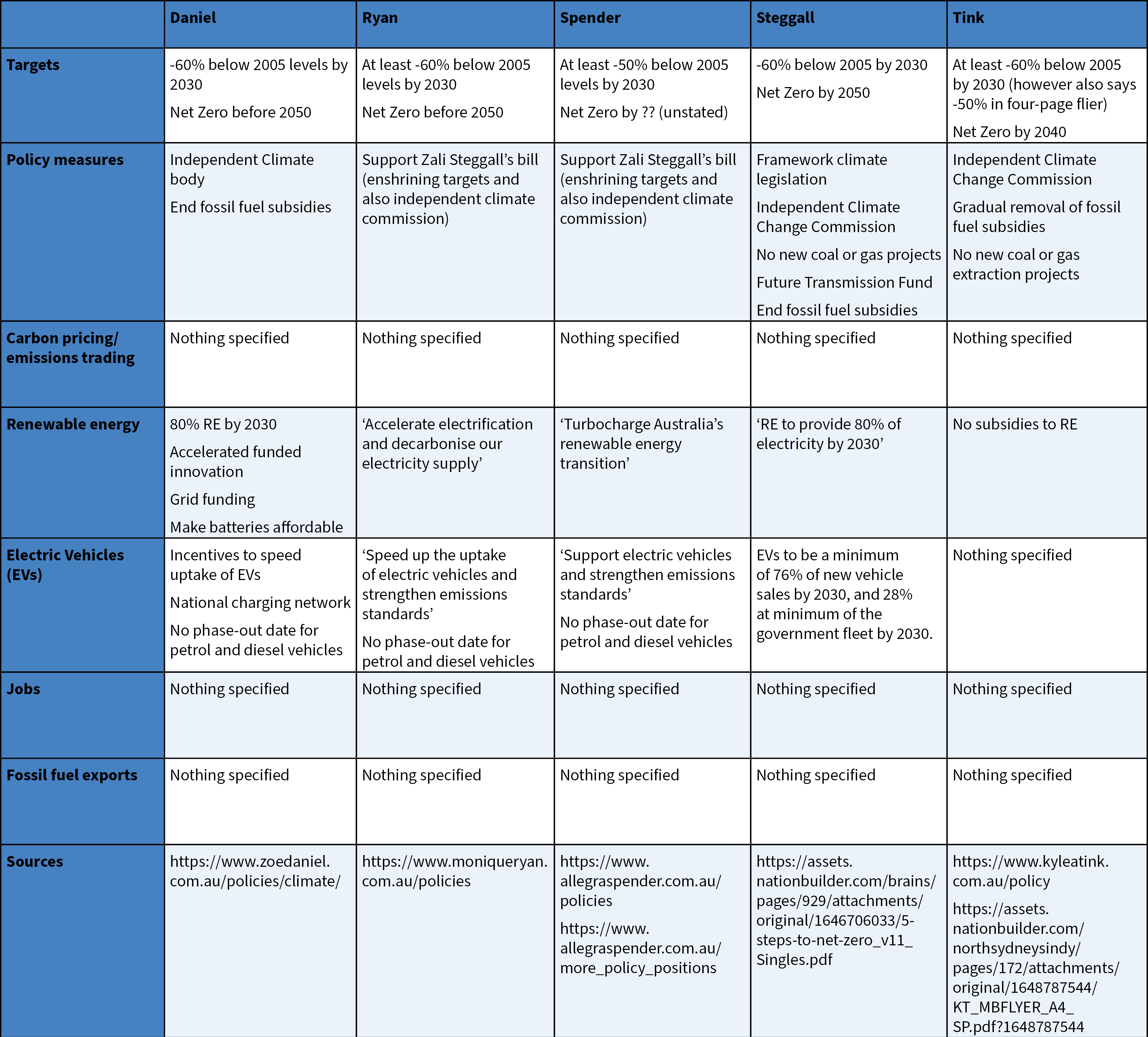

Appendices 1 and 2 enable comparison of the climate and energy mitigation-related promises of all parties and independents. Many of these are published in policy papers (if new ones emerge during the campaign, these appendices will be updated accordingly).

The Lowy Institute’s 2021 poll reveals that a majority of Australians (55 per cent) – up 8 points since 2019 – now say the government’s main priority for energy policy should be ‘reducing carbon emissions’. Further, ‘seven in ten Australians (77 per cent) support providing subsidies for the purchase of electric vehicles. An overwhelming majority (91 per cent) of Australians support subsidies for renewable energy technology development.

A sizeable majority (64 per cent) support introducing an emissions trading scheme or a carbon tax. These views have shifted significantly in the past five years. In 2016, in response to a differently worded question in the Lowy Institute Poll, only 40 per cent said they would prefer the government to introduce an emissions trading scheme or price on carbon’.36

The Coalition’s intentions are most clearly detailed in the 2022 Budget, in its Long Term Emissions Reduction Plan37 and its Technology Investment Roadmap.

Long term emissions goal

All parties and independents support the aspirational goal of Net Zero emissions by 2050 or a sooner date. None have defined pathways and measures sufficient to ensure its achievement.

Short term emissions goal (by 2030)

The crucial indicator of intended progress is the short-term national emissions target, along with measures to see this achieved.

The Coalition has not flagged any intention to strengthen its 2030 target commitment of 26–28 per cent below 2005 levels, thereby breaching requirements to do so as articulated in the Paris Agreement. It is not intending to follow international best practice by enshrining its targets in legislation.38

The Morrison government has repeatedly claimed that Australia is ‘on track to exceed its 2030 target with a reduction in emissions of up to 35 per cent projected by 2030’.39 This ‘projection’ is based on a hypothetical scenario involving unknown technologies producing cuts additional to those reductions expected from currently available technologies and those expected to be implemented at scale during the remainder of this decade.

Labor is promising a national emissions reduction outcome of -43% by 2030.40 It has not indicated that this will become a legislated target.

The Australian Greens are aiming for 75 per cent below 2005, and the independents (predominantly) for -60 per cent or more, with their targets and associated emissions reduction pathways legislated.

Neither One Nation nor the United Australia Party have offered targets, with One Nation intending for Australia to withdraw from the Paris Agreement.

Renewable energy

To ensure rapid and timely decarbonisation of power generation in Australia, we need a new Renewable Energy Target (RET) along with mechanisms (such as an emissions trading scheme) or a mandated schedule for coal plant closures.

While still referring to a RET, though one no longer exists, the Coalition offers no explicit 2030 renewables target. Labor is promising that renewables will provide 82 per cent of generated power in the national grid by 2030 – one assumes with a target. The Greens are aiming for 100 per cent ‘as soon as possible’. Only the Greens are promising the introduction of an emissions trading scheme.

The 2022–2023 Budget Papers – which mention climate change only once – outline the Government’s express mitigation intentions. There is no increased commitment to ‘clean hydrogen, CCS, batteries and large-scale solar’. The Coalition’s promise of AU$600 million for the ‘gas-fired recovery’ remains intact.

Federal funding for renewable energy through the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) and the Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC) will peak at AU$410 million in 2023–24 and then fall by 10 per cent to AU$310 million in 2025–26.41

This is roughly one percent of the projected of AU$27 billion annual defence allocation, and half the amount promised in new subsidies for fossil fuel export development.42

By contrast, Labor, in its Rewiring the Nation policy, is promising AU$20 billion for power grid upgrades and renewables, and a corporation to govern its implementation.43 It is promising to co-invest AU$100 million for 85 solar banks and spend AU$200 million for 400 community batteries.

Electric vehicles (EVs)

Transport is the source of approximately 18 per cent (or roughly 24 Mt) of Australia’s annual national emissions. This sector’s emissions have been rising since 2000. Only temporarily reduced by the ‘COVID downturn’, they are again beginning to increase.

The 2022–23 federal budget offers AU$12.3 billion for roads and AU$3.7 billion for rail infrastructure44, but almost nothing for electric vehicles – the critical path for ensuring reduction of transport emissions and fuel-cost savings.

The Coalition government is allocating AU$250 million to its Future Fuels and Vehicles Strategy.45 It claims that, with the release of this strategy, it has committed AU$2.1 billion overall to partnering with industry to support the uptake of low and zero emission vehicles.46 It is impossible to verify this statement or to find supporting figures in the current or previous budgets. The government estimates the FFV Strategy will fund an additional 400 charging stations for businesses, 1000 public stations and 50,000 for homes, an will create 2600 new jobs.47

This funding is expected to reduce transport emissions by 8Mt CO2 by 2035.48

If successful, therefore, by 2035 this initiative will reduce transport-related emissions to only one third of their current (24 Mt) annual contribution. Independent of policy, and as a consequence of the falling price of EVs, the Coalition projects EVs and hybrid plug-in vehicles to comprise 30 per cent of annual new car sales by 2030, and for some 1.7 million electric and hybrid vehicles to be on the roads by 2030.49 There is no phase-out time for petrol and diesel vehicles.

Labor is proposing an Electric Car Discount incentive scheme costing around AU$250 million over three years. It will exempt non-luxury EVs from import tariffs and fringe benefit taxes. The Shorten-era policy included a non-binding target of 50 per cent new car sales being EVs by 2030. There is no mention of this in the current policy promise, there is no phase-out time for petrol and diesel vehicles, and no projection of impacts on transport-related emissions.

Carbon levy or tax/emissions trading

Only the Australian Greens is proposing to introduce an explicit carbon price and emissions trading.

Employment

Labor is claiming its Powering Australia plan will directly and indirectly create 604,000 jobs. No other party or independent has offered a comparable estimate.

Fossil Fuel Exports

The Coalition and Labor do not mention fossil fuel exports explicitly in their climate policies, and each supports existing measures and policies to enhance production.

The Coalition has promised an additional AU$1.3 billion in subsidies to the coal and gas export sector.50 However, Labor is also promising to require coal producers to reduce their emissions via its revamping of the safeguard mechanism.51

By contrast, the Greens oppose any new coal, gas or oil development, aim to end fossil fuel exports by 2040, and to tax them in the interim.

International climate politics

The Coalition is offering nothing new here. By maintaining Australia’s current 2030 target, the Coalition will further damage Australia’s international reputation as a climate laggard. By contrast, Labor is intending to amend the target and is offering to host a future UN Climate Conference, which traditionally serves to highlight and enhance the host nation’s domestic performance.

What will the next term bring?

Climate will be a significant underlying factor in the election outcome. What happens next? The Coalition or Labor may win outright, or Labor or the Coalition may find themselves in minority government, seeking the support of Independents and Greens – as did Julia Gillard in 2010. A hung parliament and government created through a formal or ad hoc alliance with independents increasingly seems likely.

In 2010, the Gillard government's reliance on the support of the Australian Greens and four Independents to form minority government led to a significant strengthening of its climate and energy policies – including a price on carbon, substantial funding for renewables, and enduring positive institutional changes like ARENA and the Clean Energy Fund. An alliance involving the ‘teal Independents’ will almost certainly depend on agreement around toughened climate targets and associated legislation.

An incoming government, irrespective of orientation, will confront three pressures and a possible wild card for climate and energy policy.

First, targets and performance. Why Morrison has failed to shift here is unclear, given the Government’s stated expectations of ‘over-performance’. Perhaps this move will be announced during the campaign. In any case, it certainly will happen – irrespective of who wins – before the next meeting of the parties to the Paris Agreement later this year.

Second, as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Working Group II Report indicates, extreme events will inevitably intensify and require more comprehensive – and federally better coordinated – adaptive and remedial responses and funding during the next term. The mechanisms for promoting adaptation and for handling post-disaster remediation require strengthening and the pressure of further events will underscore this need.

Third, the temptation to continue to milk the fossil fuel export boom will remain irresistible given soaring gas and coal prices, and national public debt. But as climate-related public contestation and legal challenges increase, government silence and inaction here will be increasingly untenable. However, the predicted slow-down of the Chinese economy is likely to undermine the export market and further destabilise plans for subsidised support and expansion.

Last, the wild card: geopolitics. The war in Ukraine has created enduring instability in energy markets and a potential crisis for domestic energy costs. Australia’s fractured relationship with China may further destabilise our export markets for coal and iron ore. Growing contestation in the Pacific region – as evidenced by the recent deal between the governments of China and the Solomon Islands – is certain to see Australia enhance efforts to shore up its influence, including by restoring and increasing regional aid and development funding. Its regional climate-related adaptation expenditure will increase as a result.

-

Footnotes

- 1. This document was completed on 28 April and is accurate to that date.

- 2. Senior Research Fellow and Associate Professor at Melbourne Climate Futures, The University of Melbourne: 0418339947 and peterac@unimelb.edu.au

- 3. Colvin and Jotzo. 2021. Australian voters’ attitudes to climate action.

- 4. Barlow 2022. Readers survey: Climate, health and political integrity top federal issues. Also: https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/subscribe/news/1/?sourceCode=DTWEB_WRE170_a&dest=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.dailytelegraph.com.au%2Fnews%2Fnational%2Ffederal-election%2Faussie-voters-want-climate-action-what-could-decide-key-seats%2Fnews-story%2F32dbb1ba3c3228facb5bb65cb8c3478c&memtype=anonymous&mode=premium&v21=dynamic-warm-control-score&V21spcbehaviour=append

- 5. Patrick. 2022. ‘Voices of’ independents competitive in three Liberal seats.

- 6. Lowy Institute. 2021. Climate Poll 2021.

- 7. Carmichael and Brulle. 2017. Elite cues, media coverage, and public concern; and Hughes, Konisky, and Potter. Extreme weather and climate opinion: evidence from Australia.

- 8. Peterson 2021. Silver Lining to Extreme Weather Events? P.34

- 9. Murphy, Katherine. 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2017/feb/09/scott-morrison-brings-coal-to-question-time-what-fresh-idiocy-is-this

- 10. Australia Institute 2020.

- 11. Morrison 2019.

- 12. Australia, Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources. 2019. Australia’s National Greenhouse Gas Inventory: December 2019.

- 13. Australia, Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources. 2021c. Australia’s National Greenhouse Gas Inventory: September 2021.

- 14. Australia, Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources. 2021a. Australian Energy Update 2021 (September 2021).

- 15. Australia, 2021b. Australia’s National Greenhouse Gas Inventory: September 2021.

- 16. https://www.pm.gov.au/media/australias-plan-reach-our-net-zero-target-2050

- 17. Mazengarb. Michael. 2022. Australia will miss its weak 2030 emissions reduction targets.

- 18. Clean Energy Council (undated). Renewable Energy Target.

- 19. Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources. Australian Energy Update 2021. p.3.

- 20. Christoff. 2022. Mining in a Fractured Landscape.

- 21. https://www.energy.gov.au/government-priorities/energy-markets/liddell-taskforce

- 22. COAG Energy Council. 2019. Australia’s National Hydrogen Strategy.

- 23. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/apr/04/coalition-tries-for-third-time-to-let-renewable-energy-agency-fund-technologies-using-fossil-fuels

- 24. https://reneweconomy.wpengine.com/renewables-and-storage-steal-the-show-at-governments-coal-party-82178/

- 25. https://reneweconomy.com.au/projects-in-limbo-as-morrisons-promised-billions-evaporate-on-election-call/

- 26. Macintosh et al. 2022. The ERF’s Human-induced Regeneration.

- 27. https://www.canberratimes.com.au/story/7672047/integrity-of-carbon-credit-scheme-called-into-question/

- 28. Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources. Australian Energy Update 2021. p.3.

- 29. https://reneweconomy.com.au/coalition-spending-on-fossil-fuel-subsidies-tops-1-3-billion-in-first-week-of-campaign/

- 30. Clive Hamilton, Running from the Storm. 2001.

- 31. https://reneweconomy.com.au/kyoto-carryover-is-legally-baseless-international-law-experts-warn-morrison-government-72062/

- 32. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/nov/05/australia-refuses-to-join-40-nations-phasing-out-coal-as-angus-taylor-says-coalition-wont-wipe-out-industries

- 33. https://theconversation.com/the-australian-way-how-morrison-trashed-brand-australia-at-cop26-171670

- 34. https://reneweconomy.com.au/stupid-investment-un-chief-slams-coal-and-australia-in-extraordinary-climate-speech/

- 35. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-61110406

- 36. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/climatepoll-2021

- 37. https://www.industry.gov.au/sites/default/files/October%202021/document/australias-long-term-emissions-reduction-plan.pdf

- 38. Peter Christoff and Robyn Eckersley, Convergent Evolution

- 39. Budget 2022-2023. Budget Paper 1, Statement 1. P.25.

- 40. Labor. Powering Australia. P.19.

- 41. Budget 2022-2023. Budget Paper 1/ Statement 5: p.162; and https://www.cleanenergycouncil.org.au/news/federal-budget-fails-to-prioritise-rapid-transition-to-renewable-energy

- 42. https://reneweconomy.com.au/coalition-spending-on-fossil-fuel-subsidies-tops-1-3-billion-in-first-week-of-campaign/

- 43. Labor. Rewiring the Nation.

- 44. Budget 2022-2023. Budget Paper 1, Statement 5.

- 45. Future Fuels and Vehicles Strategy: Powering Choice. P.1.

- 46. Future Fuels and Vehicles Strategy: Powering Choice. P.10.

- 47. Future Fuels and Vehicles Strategy: Powering Choice. P.4.

- 48. Future Fuels and Vehicles Strategy: Powering Choice. P.10.

- 49. Future Fuels and Vehicles Strategy: Powering Choice. P.5.

- 50. https://reneweconomy.com.au/coalition-spending-on-fossil-fuel-subsidies-tops-1-3-billion-in-first-week-of-campaign/

- 51. https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/labor-will-require-coal-miners-to-pay-to-reduce-their-carbon-emissions-20220424-p5afq7.html

-

References

Australia, Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources. 2019. Quarterly Update of Australia’s National Greenhouse Gas Inventory: December 2019.

Australia, Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources. 2021a. Australian Energy Update. September 2021

Australia, Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources. 2021b. Future Fuels and Vehicles Strategy: Powering Choice. 2021

Australia, Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources. 2021c. Quarterly Update of Australia’s National Greenhouse Gas Inventory: September 2021.

Australia Institute. 2020. Polling – Bushfire crisis and concern about climate change, 23 January.

Australian Government. 2021. Australia’s Long-term Emissions Reduction Plan: Whole-of-Economy Plan for net zero emissions by 2050.

Australian Government. 2021. Australian Energy Update 2021.

Australian Government. 2022. 2022-2023 Budget Paper 1, Statement 5.

Australian Greens. 2022. A bold build for a strong clean green economy.

Australian Greens. 2022. Tackling the Climate Crisis.

Australian Greens. 2022. Public Ownership.

Barlow, Karen. 2022. Readers survey: Climate, health and political integrity top federal issues. The Canberra Times. 27 February 2022.;

Carmichael J.T. and Brulle R.J. 2017. Elite cues, media coverage, and public concern: an integrated path analysis of public opinion on climate change, 2001–2013. Environmental Politics. Vol. 26(2). pp.232–52.

Clean Energy Council. Renewable Energy Target. At: https://www.cleanenergycouncil.org.au/advocacy-initiatives/renewable-energy-target

Christoff, Peter. 2022. Mining in a Fractured Landscape: the political economy of coal in Australia. Ch.13 in Jakob, M. and Steckel. J (eds). The Political Economy of Coal: Obstacles to Clean Energy Transition. Oxford: Routledge/ Earthscan

Christoff, Peter and Robyn Eckersley. 2021. Convergent Evolution: Australia and the UK Climate Change Act. Climate Policy, DOI: 10.1080/14693062.2021.1979927

COAG Energy Council. 2019. Australia’s National Hydrogen Strategy.

Colvin, R. M. and Frank Jotzo. 2021. Australian voters’ attitudes to climate action and their social-political determinants. PLOS One. At: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0248268

Crowe, David. 2019. Deputy PM slams people raising climate change in relation to NSW bushfires Sydney Morning Herald, 11 Nov 2019.

Daniel, Zoe. 2022. Policies. At: https://www.zoedaniel.com.au/policies/climate/

Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources. 2021. Australian Energy Update 2021, Australian Energy Statistics, September, Canberra.

Hamilton, Clive. 2001. Running from the Storm: the Development of Climate Policy in Australia. Sydney: UNSW Press.

Hughes L, Konisky D.M, and Potter, S. 2020. Extreme weather and climate opinion: evidence from Australia. Climatic Change. vol. 163(2):723-743,

Labor. Undated. Powering Australia.

Labor. Undated. Rewiring the Nation: More jobs, lower prices.

Liberal 2021. Our Plan – Backing Regional Australia.

Liberal 2021. Our Plan – Delivering Infrastructure.

Liberal 2021. Our Plan – Lower Prices

Liberal 2021. Our Plan – Protecting our Environment

Lowy Institute. 2021. Climate Poll 2021.

Macintosh, Andrew; Don Butler; Megan C. Evans; Pablo R. Larraondoc; Dean Ansella and Philip Gibbons. 2022. The ERF’s Human-induced Regeneration (HIR): What the Beare and Chambers Report Really Found and a Critique of its Method. ANU Law.

Mazengarb. Michael. 2022. Australia will miss its weak 2030 emissions reduction targets, new data shows. ReNew Economy. 22 April 2022

Morrison, Scott. 2019. Scott Morrison says he has acknowledged the impact of climate change ‘all year’. The Guardian. 12 December 2019.

Murphy, Katherine. 2017. Scott Morrison brings coal to question time: what fresh idiocy is this?. The Guardian. At: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2017/feb/09/scott-morrison-brings-coal-to-question-time-what-fresh-idiocy-is-this

Patrick, Aaron. 2022. ‘Voices of’ independents competitive in three Liberal seats. 20 January 2022. Australian Financial Review.

Peterson, Lauri. 2021. Silver Lining to Extreme Weather Events? Democracy and Climate Change Mitigation. Global Environmental Politics 21:1.

Ryan, Monique. 2022. Policies. At: https://www.moniqueryan.com.au/policies

Spender, Allegra. 2022. Policies. At: https://www.allegraspender.com.au/policies

Steggall, Zali. 2022. 5 Steps to Net Zero: How Australia can accelerate our path to net zero and prosper in the new economy. At: https://www.zalisteggall.com.au/climate

Steggall, Zali. 2022. New Economy: How Australia can prosper through a sustainable, innovative and inclusive approach to business.

Tink, Kylea. Policies. At: https://www.kyleatink.com.au/policy

-

Appendix 1: Mitigation policies and promises

Accurate to 28 April 2022

-

Appendix 2: Independents’ policies and promises

Accurate to 28 April 2022

Download this briefing paper as a PDF.