With a strong vision, community input, and the power of philanthropy, eye health is improving and trachoma is being eliminated in Indigenous communities.

The commitment and generosity of individual donors, foundations and private trusts are making equitable eye health for all communities possible. Thanks to philanthropic support, Professor Hugh Taylor and his team at the Indigenous Eye Health Unit (IEHU) are working with Australia’s Indigenous population to eliminate avoidable blindness and vision loss, including trachoma.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander eye health is improving and trachoma, the highly transmissible bacterial infection that causes preventable blindness, is close to being eliminated.

Trachoma disappeared from mainstream Australia over 100 years ago, it persists in remote Indigenous communities and remains one of the leading causes of blindness. In 2007, national trachoma rates in Indigenous communities were a sobering 21 per cent.

Today, however, that figure is down to 4 per cent.

How? The work done by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and organisations with the support of the Indigenous Eye Health group (IEH), an initiative founded and led by Melbourne Laureate Professor and Harold Mitchell Chair of Indigenous Eye Health at the University of Melbourne, Hugh Taylor, supported by philanthropy.

Since its inception, nearly 15 years ago, a total of 127 donors have gifted over $14.2 million to the initiative, including supporting IEHU’s two major projects: the Roadmap to Close the Gap for Vision and Trachoma Health Promotion. This generous funding has been instrumental to the progress that has been made.

Elimination from the ground up

Established in 2008, Professor Taylor’s vision for IEH was always to provide equity in eye health (‘Close the Gap for Vision’) and fully eliminate trachoma for Indigenous Australians.

And this meant looking at eye health in its totality. First, they undertook a comprehensive national eye health survey, using the results – which revealed that Indigenous populations suffered six times more blindness than mainstream Australia and 94 per cent of vision loss was preventable or treatable – to develop a multi-faceted approach to addressing a range of systemic issues contributing to poor eye health and vision loss.

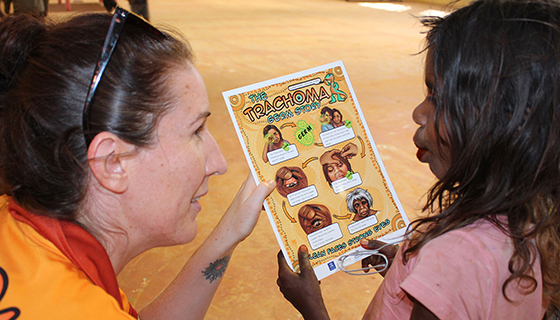

Working in partnership with community, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations and leaders to co-design solutions, a plan was established - The Roadmap to Close the Gap for Vision, and work begun to provide greater accessibility to eye services and treatment and the promotion of positive hygiene practices in local communities.

This included, for trachoma, working with government departments of housing and education to incorporate hygiene messages into curricula, upgrade washing facilities at schools, and ensure the repair and maintenance of blocked drains or faulty taps within homes.

With trachoma rates now reduced to 4 per cent, and eliminated in many communities, and blindness in general reduced by half, the results are nothing short of remarkable – which Professor Taylor puts down to the ethos of the project, made possible by philanthropy.

"We've made good progress in providing antibiotic treatments, and there has been particular emphasis on the health messaging. We've developed health education, health promotion and surgery. Putting all of that together, I feel our success can be attributed to a multipronged approach.”

“Philanthropic support gave IEH the opportunity to look at the challenges of eye health in a whole of system and holistic way,” he says.

As well as being fully philanthropically funded in its first 5 years, IEH still receives around half its funding from generous donors.

The independence and flexibility philanthropic support given us from the the start has shaped our progress. It has enabled us to do the groundwork, the research, and the community engagement and consultations to work through what needed to be done to improve eye health. That is where it has been so truly effective.

- Professor Hugh Taylor

Advancing policy

Of course, government funding is essential to the sustainability of the eye care system. And another critical focus – and achievement – of the IEH is advocacy, engaging governments at a local, state and federal level to ensure the issues of eye health are understood and steps to address them are pursued.

But that too has been a flow on effect from early support. The Australian Government commitment in 2019 to a Long-term National Plan to eliminate avoidable blindness in Indigenous communities by 2025 is one key example.

“A lot of the progress we’ve made with the Australian Government is thanks to the independent support we've had. We can raise issues with ministers without fear because they can't cut your funding off tomorrow. With time, the Government has seen the value and importance of our contributions. In turn, that builds impetus for them to provide funding to support the eye services provided by the sector.”

Beyond eye health

As well as reducing rates of trachoma, IEH and its systemically led, ground-up approach is achieving positive impact beyond eye health too.

Community education centred on positive hygiene practices creates a virtuous circle in protecting against other transmissible diseases, including skin and gastro-intestinal infections. Work from the initiative was even adapted for COVID-19 campaigns in remote communities.

Their holistic approach is also being replicated in other areas of primary healthcare, says Professor Taylor.

“We're working across the whole spectrum of eye health for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, as well eye health in the non-Indigenous Australian population. But we're also talking to other groups working on more speciality areas in Indigenous health – areas like ears, the heart and diabetes – to see which lessons we’ve learnt from eye care can be transferred to these other in-need areas.”

The snowball effect of philanthropy

The progress made by the IEH since its inception has been remarkable. But this wasn’t always a given. While Professor Taylor had no question about whether he would set up the initiative, handing back his tenured position as Head of Ophthalmology at the University of Melbourne to do so, funding was very much in question.

Thankfully, within months of establishing the initiative Professor Taylor found his first vote of confidence: five years of funding from the Harold Mitchell Foundation, bolstered shortly later by an additional grant from The Ian Potter Foundation.

"That really set us up", he recalls. "One thing after another, we grew and developed."

“We have had the backing of the Deans over time, from the University of Melbourne as a whole, and the phenomenal ongoing support from donors and foundations. I’m incredibly thankful for all this support because it has allowed us to accelerate our work and get successful outcomes sooner."

“There are a lot of people who want to see things done well in the Indigenous health space, but they just don't know where or how to do it. I think people have seen what we are doing and how we are doing it, and so they have been very willing to support us. It’s quite extraordinary.”

Professor Taylor also observes that “the context for contribution and achievement in Aboriginal and Torre Strait Islander health now is different from when IEH was established. First Nations leadership, ownership and determination are now key elements for advancing health and well-being. Our approach has continued to develop as we constantly work to being the most effective allies we can.”

Eyes on the prize

The dedication remains. With additional philanthropic support pledged until 2025, Professor Taylor is redoubling his efforts to eliminate trachoma entirely and ending avoidable blindness and vision loss.

"We've seen big improvements, but we still need to get that trachoma prevalence rate lower. We need to ensure every Indigenous Australian with diabetes has an annual eye examination and that all Aboriginal people have an eye exam every two to three years. Anyone with sight problems needs to be seen right away. That's the standard we're looking at for First Nations communities across Australia and this system of care should be led, owned and determined by First Nations people."

With much to go on with, Professor Taylor has little time to look back. However, when he does reflect on the journey of IEH he feels extraordinarily privileged to have contributed and be witness to the progress.